This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.

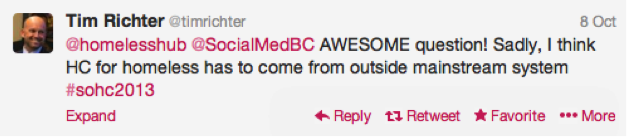

During our Tweet Chat in October the following question was raised by Social Medicine BC:

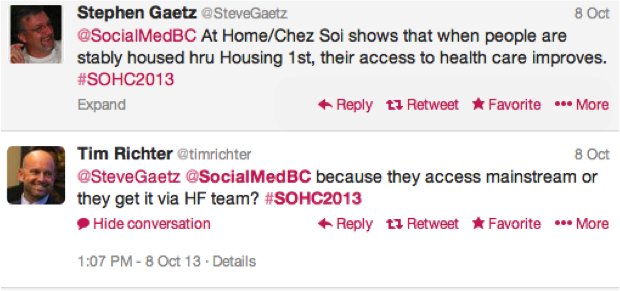

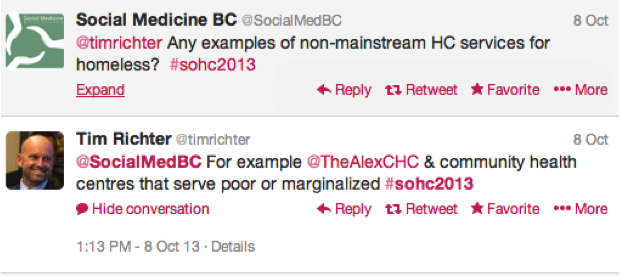

The discussion and answers from the panelists included:

Let’s unpack these answers a little more.

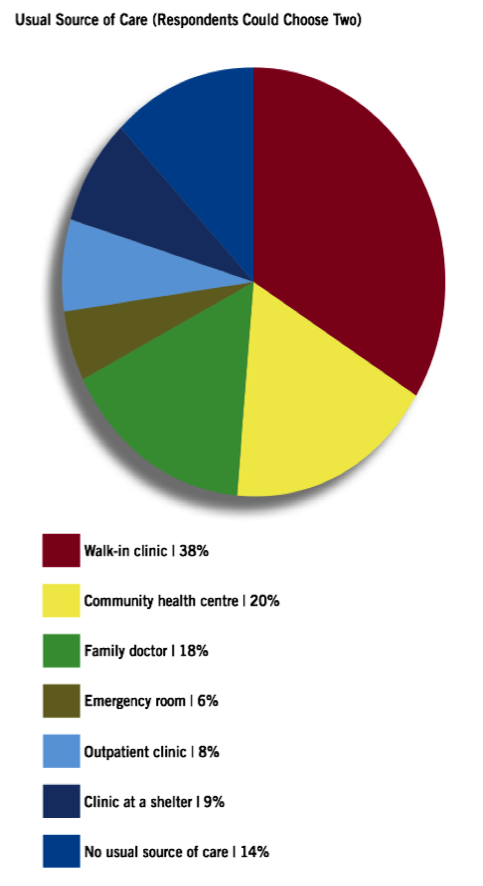

A stand-out study in Canada – although the data is getting slightly dated now – is from Street Health in Toronto, entitled “Access to Primary Health Care Among Homeless Adults in Toronto, Canada: Results from the Street Health Survey”. The report looked at the significant barriers people experiencing homelessness face when trying to access health care. One of their findings was that the longer an individual spent on the street the less likely it was that they would have a primary physician. Many homeless people rely on walk-in clinics and emergency rooms for their health care, which is a very expensive means of obtaining treatment.Shelters and homeless-serving agencies can assist by building health care treatment – through mobile clinics, street nurses or staff physicians into their overall service provision planning.

The report also found that lack of an OHIP (Ontario Health Insurance Plan) card prevented many people from obtaining necessary treatment. Reducing dependency on the ID card – through barrier-free access to health care – can greatly reduce overall spending on health care, especially if preventative measures are taken into account.

A similar study in Winnipeg, “The Winnipeg Street Health Report 2011”, saw similar issues.

The report found that, “Half of respondents had to see a doctor or medical provider in the past year just to get forms filled in. Fifteen per cent (15%) had to see a medical staff for forms at least three times. With 72% of respondents not having a family doctor or receiving care from a community health clinic, getting all the necessary paperwork complete can be impossible.”

Additionally:

- “Thirty-six per cent (36%) of homeless people we interviewed said they had been judged unfairly or treated with disrespect by a doctor or medical staff at least once in the past year.”

- “Thirty per cent (30%) of respondents believed they should be eligible for disability assistance (that is, they had a disability or serious illness that is continuous or recurrent and it expected to last more than one year) but were not receiving it. “

This short paper, titled “Homelessness and Access to Health Care: Policy Options and Considerations”, looked at “the current health situation of the homeless population in Canada, along with the characteristics of health care use among members of this group…[It provides] an overview of the various policy options that may work to effectively address the unique health issues of the homeless population.”

New research from “The Effect of Socioeconomic Status on Access to Primary Care: An Audit Study” shows that “within a universal health insurance system in which physician reimbursement is unaffected by patients’ socioeconomic status, people presenting themselves as having high socioeconomic status received preferential access to primary care over those presenting themselves as having low socioeconomic status [SES].” In this study, health care practitioners offices were phoned and presented with different scenarios related to economic and health status. Those presenting with a higher SES and lower health concerns were offered appointments more frequently than callers from a lower socioeconomic status who had chronic health issues. This research shows that access is a systemic issue that must be addressed by governments at the provincial/territorial and national levels.