In this bi-weekly blog series, I explore recent research on homelessness, and what it means for the provision of services to prevent or end homelessness. Follow the whole series!

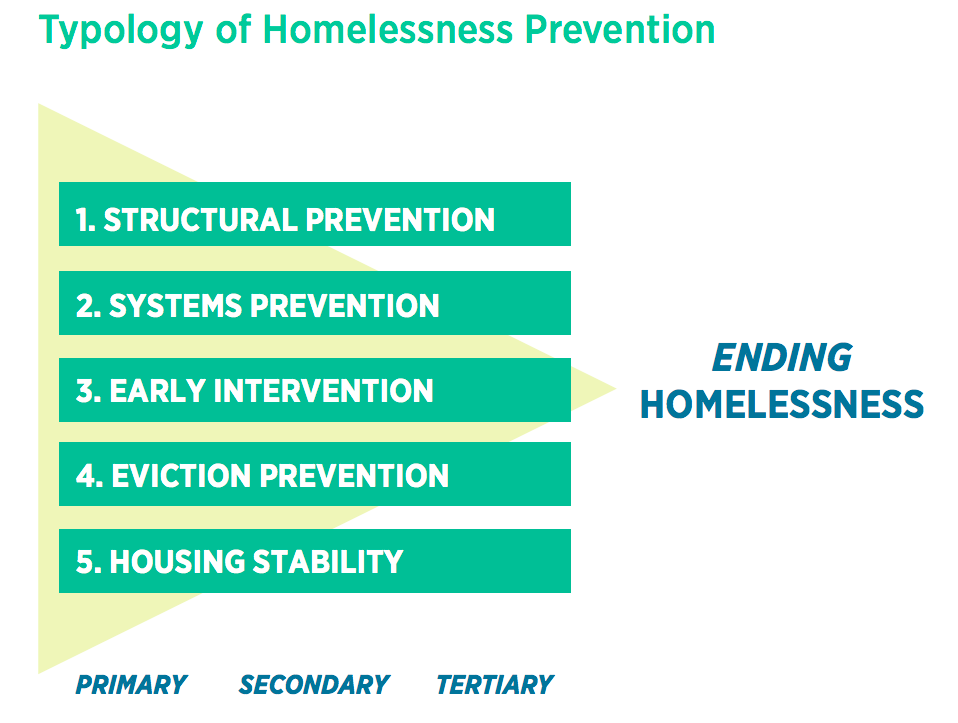

The evidence base for ending homelessness is growing rapidly with significant research and evaluation being conducted around Housing First. This research is now being refined among particular populations such as Housing First for women, youth, or Indigenous Peoples. Conversely, the evidence base for homelessness prevention is far less refined. The 'what', 'how', 'when', and 'who' of preventing people from ending up homeless in the first place is still evolving as the realization hits that a downstream approach like Housing First is best complimented by diverse and effective upstream approaches.

Thanks to data on the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-housing Program (HPRP) out of the United States, we can start to do some analysis. This program supports both homelessness prevention through tools such as temporary financial support, and rapid-rehousing through case management and legal support. These services fall under the categories of "Eviction Prevention" and "Early Intervention" in the 'Framework for Homelessness Prevention'.

To see if they could predict whether recipients of HPRP were successfully re-housed or stayed housed, Molly Brown and colleagues from DePaul University conducted a study of 'Housing Status Among Single Adults Following Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing (HPRR) program Participation in Indianapolis'. As more research has been done on prevention of family homelessness, the focus was on single adults, using data from 515 HPRP recipients.

Between the two programs, 23.7% of homelessness prevention participants experienced housing loss, and 31.4% of rapid re-housing participants had now been housed at completion. The authors note that these rates are lower than national level outcomes through these programs. Here's what they found:

- The greatest predictor of housing success was participants staying engaged with the program to completion. This points to the fact that these types of light touch programs are not necessarily successful for those with high needs.

- Stronger finances were highly predictive of housing success. Every $100 more of monthly income increased odds of remaining housed by 11%. This also related to providing longer-term and higher levels of emergency income support.

- Next to engagement and income, case management was the highest predictor of rapid-rehousing success, meaning that this is a promising practice for prevention, not just Housing First.

Ultimately, the findings provide a number of considerations for evolving effective prevention of housing loss. I was particularly struck by the limitations of these programs to prevent housing loss for those with complex needs, such as mental health concerns or substance use. Where the programs were designed to be light touch, rapid, and low barrier, there is also apparently a need to do some form of screening for those who may need greater support to prevent a first episode of homelessness from becoming chronic. That's not to suggest a further screening for eligibility, but some form of early identification of higher support needs.

While housing loss prevention in this case worked for the majority of recipients, there is still more work needed to make it work for all.