This question came from Susan V. via our latest website survey.

Homelessness in northern and remote communities is distinct from urban homelessness in a few different ways. As Alina Turner, PhD wrote in a 2014 blog post, rural homelessness is an “invisible, and diverse yet prevalent issue.” In these areas, housing stock and services are limited; economic changes are felt much more deeply; and disasters take a higher toll. Furthermore, there exists what Turner calls the “migration solution”:

One of the strategies used by those who experience homelessness in rural areas is migration to nearby communities or larger cities with better housing, services, employment and education opportunities. In fact, they are encouraged to relocate by their families and friends and support workers; community leaders and public opinion may push "problem individuals" out as well. This is certainly the case for victims of domestic violence who have little choice to escape abusive situations in small communities. Because larger centres also offer more "anonymity" for those seeking help, migration is often seen as a viable solution. Of course, this requires uprooting from one's home community and losing important social ties and connections.

Youth from rural communities are particularly likely to move to larger cities in search of housing, jobs, services and/or independence. (LGBTQ2 youth tend to move to urban centres to live in places that are more progressive.) A Youth Centres Canada fact sheet estimates that between 40% and 50% of youth experiencing homelessness are from rural communities.

If housing becomes an issue in a rural context, it is crucial for youth to have options in their own community if they want and are able to stay. The following are just a few of the programs being developed by agencies in rural communities to help address youth homelessness.

Transitional programs

Supportive and transitional housing, depending on youth’s needs, have been found to be helpful for youth at-risk of or currently experiencing homelessness – especially in the Foyer model. Large supportive or transitional housing options, however, aren’t always available in rural settings. A 2009 U.S. survey of youth service providers found that the use of “host homes” and outreach were considered crucial strategies in addressing youth homelessness. A host home is a place where the owner lives and has a spare room that they are willing to offer to youth in need. Host homes “are utilized as a low-cost, community-engaging strategy to create housing destinations when the use of congregate or scattered site apartment models are not available as an option.”

Host homes look different depending on the needs of and availabilities within a community, but tend to focus on youth’s short-term housing needs. In the UK, Depaul runs a program called Nightstop, which aims to prevent youth 16+ from rough-sleeping and provides private room stays with families/hosts. At 33 locations throughout the UK, Nightstop provided beds to 13,500 youth in 2014 and operates mostly with volunteer hosts and drivers. This year, a feasibility study concluded that the program could be extended to 14- and 15-year olds with support from local authorities and police.

In the Halton Region of Ontario, Bridging the Gap runs a host home program for youth 16-24, who can stay in these homes for up to four months. The same agency provides transitional housing (Bridge Home) and case management for youth who need more long-term housing and support.

Preventative services

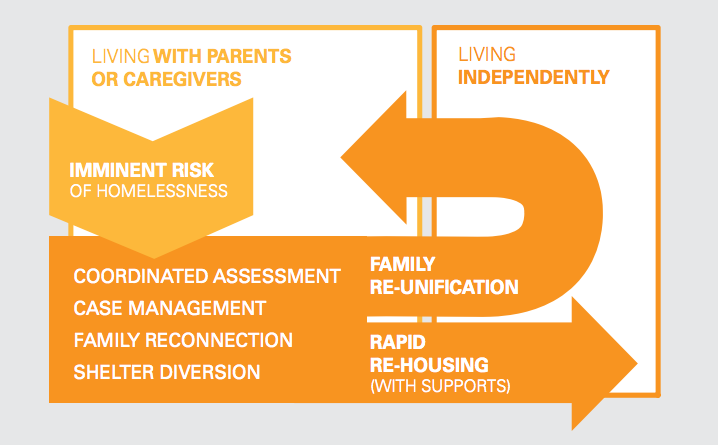

In Coming of Age: Reimagining the Response to Youth Homelessness, Gaetz emphasized the importance of shifting to a preventative response (options pictured right). By encouraging youth’s resilience and “protective factors,” it is possible to prevent youth from experiencing homelessness at all. He writes:

Protective factors include a person’s individual qualities and personality traits that help them persevere in the face of stress, traumatic events or other problems (Smokowski et al., 1999; Crosnoe et al., 2002; Bender, 2007; Gilligan, 2000; Ungar, 2004). Protective factors help reduce or mitigate risk, ultimately contribute to health and well-being and may include decision-making and planning skills, as well as higher levels of self-esteem (Lightfoot et al., 2011), positive family and peer relations, engagement in school and other meaningful activities and lower levels of drug use or criminal involvement (Thompson, 2005).

One rural example of preventative services is RAFT’s Youth Reconnect program, which connects youth to workers that ensure they can find housing and other services in their communities. The agency also provides school-based programming, transition support for youth exiting the child welfare system, and a hostel that features plenty of social and community-based programming.

Housing First for youth

Housing First is being adopted as policy throughout Canada, after demonstrating its effectiveness with people experiencing chronic and episodic homelessness. Though Housing First sometimes requires creativity to function in rural communities, it is possible. As I highlighted in a previous post on rural homelessness, Waegemakers Schiff and Turner (2014) made the following suggestions (among others) in their report on Housing First feasibility in rural communities:

-

Creating materials that speak to the realities of smaller communities (ie. focus less on ACT and other urban models);

-

Leveraging multiple funding streams, including support from private landlords and homeowners; and

-

Advocating for a systems-level approach to homelessness.

Recently, Gaetz (2014) called for the Housing First model to be used with youth as well. As long as programs are adapted to rural contexts and youth participants, they can be very effective. RAFT provides Housing First services to youth 16-24 throughout the entire Niagara region.

What rural youth homelessness interventions are taking place in your community? Sign up for our Community Workspace and share what you and and others and working on.

Related posts:

How can we develop policies that address both urban and rural homelessness?

How can I find relevant research and resources on rural homelessness?

How can Housing First work in rural communities?

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.

Photo credit: Coming of Age: Reimagining the Response to Youth Homelessness in Canada