This question was asked anonymously via our latest website survey: What are some ways that affordable housing has been built, even in these very austere times?

On this website, my peers and I have written extensively about the lack of affordable housing in Canada and how it’s a key contributor to homelessness. Housing is considered affordable by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Company (CMHC) if a household spends less than 30% of its pre-tax income on adequate shelter – but what a household’s income is varies wildly.

Right now, Canada relies heavily on the private market for its housing supply. Plenty of new units have been developed across the country and real estate is booming in cities like Toronto and Vancouver, but the majority of those options simply are not available to many people in medium to low income levels. Decades ago, the federal government pledged funding for affordable social housing, but such funding has been rapidly declining since 1993.

In the State of Homelessness in Canada 2014 report, Gaetz, Gulliver-Garcia and Richter highlighted the fact that decades of disinvestment in new affordable housing projects has resulted in 100,000 units not being built. There have been some successes, however, that were also discussed in the report:

As of March 31st 2014, the federal government reports that 183,642 households were no longer in “housing need” (CMHC, 2014)…The majority of these households were in Quebec (137,481 units). It is important to look at what this means. Approximately 110,000 of the households assisted in 2010-2011 in Quebec were helped by the province’s small although laudable housing benefit, Allocation Logement. The maximum amount per household is currently $80 per month, but the average in 2010-2011 was just $56 (Société D’Habitation Du Québec, 2011; 2014).

These numbers also include units that were funded under renovations programs and therefore are not new units of housing (although improvement of poor housing conditions is certainly an important and admirable goal, which may lead to the prevention of homelessness).

Similarly in British Columbia, 813 households were assisted under the same program between 2012 and 2013. Of those, 165 were new builds and 609 were units that were “renovated, rehabilitated or repaired.” So while this is necessary assistance, it doesn’t lead to the development of lots of new housing.

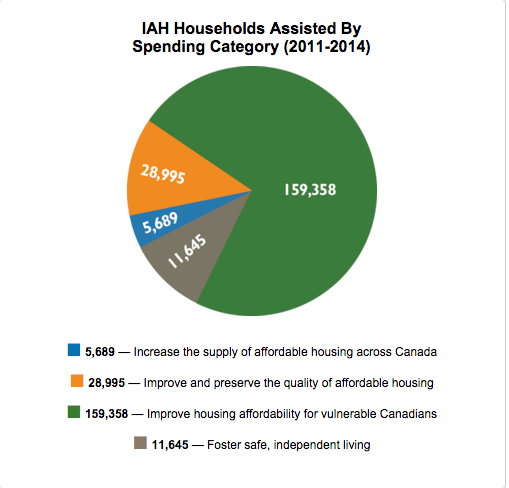

Today, most affordable housing funding comes from the Investment in Affordable Housing (IAH), and most of that money goes to improving and modifying existing housing (as shown on the right). Given the declining quality of much of Canada’s social housing, these are crucial investments, but they only maintain what we already have. The CMHC lists a number of country-wide agreements by province and territory.

Affordable housing can and is being built

Through the development of affordable housing strategies and partnerships between government and developers, affordable housing is being built.

In many areas, affordable housing is often built on property owned (or previously owned) by municipalities. In Toronto, the municipal government website lists affordable housing developments currently under construction. Much of the affordable housing in the city is repurposed – the most well-known example is the Pan-Am Games Athletes’ Village buildings. In 2011, two non-profit agencies, Wigwamen and March of Dimes, purchased one building and will be offering the units well below market pricing. Other partnerships are in the works throughout the province, including Barrie, Niagara region and Kingston.

As Catherine McIntyre wrote for Torontoist, the rate at which housing is being built simply isn’t keeping up with demand:

Since 2010, fewer than 3,700 new affordable units have been built in Toronto, while about 94,000 individuals and families are waiting for subsidized housing. Of the affordable units that do exist, 400 are currently uninhabitable and another 7,500 are on pace to be boarded up in the next decade.

In any area, the ability to build new housing requires cooperation between levels of government. Back in March, the Ontario government announced its long-term affordable housing strategy, which proposes inclusionary zoning: requiring developments of certain sizes to include a percentage of affordable units. Development companies are currently opposing this inclusion, and it remains to be seen if the province will enforce it or not. Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver municipal governments have adopted inclusionary housing policies, but higher level government support is needed to truly make them effective. Hopefully between provincial and territorial commitments to affordable housing and the increase in federal support and funding, we will see much more built in the coming years.

Related posts:

How can we incentivize building more low-end housing?

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.