One of the key issues facing homeless or marginally housed young people is the difficult task of “transitioning away from homelessness.” What exactly this means and when it begins and ends is not easy to figure out, and the definition can change depending on who you talk to. Another important issue is trying to understand the factors that help young people who have experienced homelessness succeed in this transition (as well as the barriers they face, which it turns out are a lot).

A recent research project co-lead by Jeff Karabanow from Dalhousie University, Sean Kidd from CAMH, and Jean Hughes from Dalhousie sought to understand these questions better. The research was supported by SSHRC and the W. Garfield Weston Foundation and was conducted in collaboration with service organizations in Toronto and Halifax − Covenant House Toronto, LOFT Community Services, SKETCH, Ark, and Supportive Housing for Youth Mothers (SHYM).

The project interviewed 51 young people from Toronto and Halifax as they transitioned away from homelessness. Each young person was interviewed 4 times throughout the course of a year about their experiences in finding their way towards housing and stability. The study focused on young people who were between the ages of 16 and 25 and who had experienced at least 6 months of homelessness in their past. We also wanted to focus on youth who were at the beginning of the transition process so we only interviewed youth who had been in housing between 2 months and 2 years.

Most policy makers, researchers, service providers and young people would agree that the core part of a successful transition away from homelessness is stable housing. The interviews confirmed this with many young people talking about how housing was essential to building their confidence, and because it provided a necessary foundation from which to build towards their other transition goals like getting back into school, finding a good job, addressing addictions issues, getting healthy, or reconnecting with family.

However, we also found that the process of exiting homelessness actually started long before youth found stable housing and that it began with a traumatic event or personal turning point that really inspired them to dedicate themselves to the difficult task of getting away from the street. Youth encountered so many barriers to exiting homelessness that success was only possible when they were extremely committed and focused − a commitment that can be hard to maintain without a lot of help and support. This raises important questions about what we can do collectively to make this process less difficult for motivated young people, a point I will return to.

A related issue about figuring out when transitions begin and end is that even though young people found their way into housing, maintaining it was often very difficult. Around 25% of the young people we interviewed lost their housing during the year of the study and many of the rest felt like they were always on shaky ground. That means that many of the young people we had talked to had been “transitioning away from homelessness” for years with the overall process being two steps forward, one step back (or sometimes even two or three steps back).

The main reasons that the youth we interviewed lost their housing were:

- Roommate issues − such as roommates not paying their portion of the rent or conflict with each other. With limited housing choices young people were often having to live with people who they didn’t know very well or who might be involved with crime or drugs.

- Controlling or exploitative landlords who would try to impose rules over and beyond the province’s Landlord-Tenant rules (telling people not to shower so much, or when they could come and go from their own apartment), or who would not adequately maintain the unit.

- Outstanding legal trouble from years back that finally results in jail time. Even a short time behind bars could lead youth to lose their housing.

- Trouble with affordability − young people who couldn’t find subsidized housing and who were paying market rent would often struggled to make ends meet, particularly in Toronto’s high-priced rental market.

- Addictions and mental health relapses or problems were an ongoing issue for a number of the youth we talked to.

Two other central issues that young people encountered were social isolation and difficulty finding employment. Youth experienced loneliness and isolation because part of making the transition from homelessness usually involved cutting themselves off from old friends. Young people often also broke ties with service agencies like shelters or drop-ins because they didn’t want to hang around those places anymore. This isolation might trigger a relapse in drug or alcohol problems, or increase common mental health issues among this group such as depression, anxiety, or PTSD.

Finding employment was also a serious issue. Youth unemployment rates have been over 17% in Ontario and Nova Scotia for the last few years and this is a group who are at a particularly disadvantage because of limited work experience and criminal records (often for minor crimes related to survival or drug use, as well as because of the overpolicing of people who are poor or homeless). Unemployment hurt young people financially, but it also lead to feelings of hopelessness.

I should point out that it is not all doom and gloom and there were many inspiring stories of resilience and strength − young people that managed to get themselves into a stable housing situation and to begin the process of working towards their personal goals like employment and education. We found that those who were successful (even though it was always a struggle) were those who felt they had the unconditional support of a family member, stable friend/romantic partner, or case worker. Sadly, many of the people we interviewed didn’t have such a person. We also found that supportive and subsidized housing had a very positive impact by lessoning the financial burden, providing support, and by having more flexible rules that allowed for bumps in the road.

Our main recommendations for changes to policy and services are:

- Overall enhancement of ongoing supports (e.g. caseworker support, employment programs) that do not disappear when youth “age out” of the youth social service system at age 25. When possible, these supports should be decoupled from crisis-focused services aimed at currently street-involved youth (the main source of social service support at the moment).

- Interventions and supports need to address the barriers created by homelessness such as trauma, limited work experience and police records. Access to support also needs to be streamlined in order to capitalize on transition points and to maintain momentum. There was nothing more demoralizing to youth then to make big changes in their lives just to find themselves blocked around the next corner. Particular service areas include:

-

-

Improved access to affordable housing and support in navigating tenancy.

- Improved access to psychological and trauma counselling.

- Improved access to record suspensions (formerly called pardons), as well as follow through on policies that remove non-conviction records from police records checks.

- Improved access to family counselling and reconciliation services.

- Improved access to drug treatment programs.

- Improved access to skills building, apprenticeship and work opportunities.

- Improved access to programs that foster valued identities, skill building, social interaction and healthy entertainment (sports, art, bike repair, etc.)

-

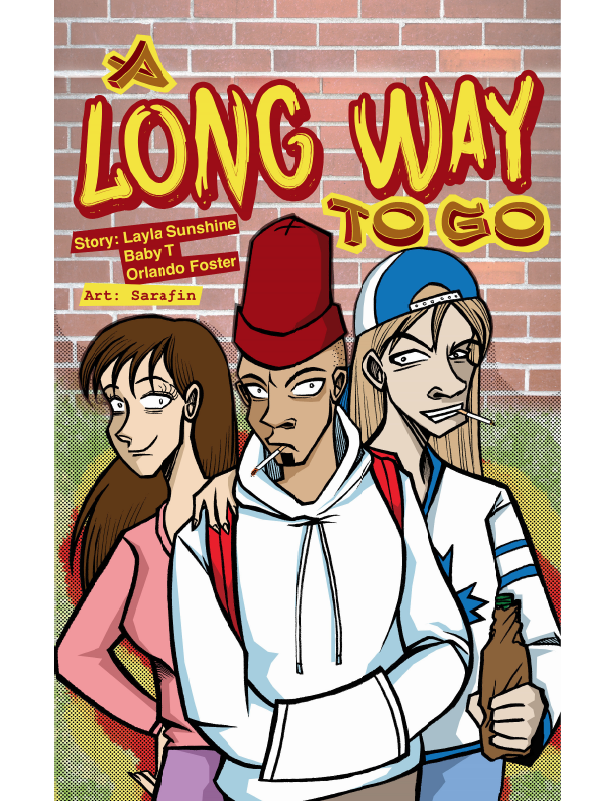

If you are interested in finding out more, please take a look at an Executive Summary of the research and also check out our comic book! The comic is called ‘A Long Way to Go’. A group of youth from the study wrote the story to highlight themes from the project and it was beautifully illustrated by comic artist Saraƒin. The comic was launched at a gallery event in Toronto hosted by SKETCH that was very successful with amazing performances by young people with lived experience and attendees from the City of Toronto, the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services, and service providers from across the city. The success of the research project, comic, and launch event underscore the exciting things that can be achieved when researchers, service agencies, and people with lived experience collaborate to make an impact.

For more information or for access to a print ready version of the comic contact tyler.frederick@uoit.ca. Additional publications from the research include (with more to follow):

How stable is stable? Defining and measuring housing stability

Brief Report: Youth pathways out of homelessness: Preliminary findings