Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, and 2-Spirit [1] (LGBTQ2S) youth are disproportionately represented amongst homeless youth populations across the globe. Approximately 25-40% of youth experiencing homelessness in North America identify as LGBTQ2S (Abramovich, 2012; Ray, 2006; Cochran et al., 2002). However, it is difficult to know exactly how many LGBTQ2S youth are experiencing homelessness at any given point in time, for a variety of reasons. For example, support services, shelters, and street needs assessments often do not include questions about LGBTQ2S identity, and if they do, many queer and trans youth may not feel safe disclosing their gender or sexual identities, due to safety concerns. Hidden homelessness is also a significant concern for LGBTQ2S youth, especially those living in rural communities, making it highly unlikely that they would be included in statistics and key reports on youth homelessness.

Identity-based family conflict resulting from a young person coming out as LGBTQ2S is a major contributing factor to youth homelessness (Abramovich, 2012; Quintana, et al., 2010; Ray, 2006). LGBTQ2S youth are particularly vulnerable to mental health concerns, and face increased risk of physical & sexual exploitation, substance use & suicide (Denomme-Welch et al., 2008; Ray 2006). Transgender youth have needs that are distinct from those of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. For example, they may need transition related health care, including access to hormones or surgery, or help getting ID and legal name change sorted out. Shelter workers tend to struggle most with issues regarding access to services for trans and gender non-conforming youth.

Through my research, I have found that factors such as institutional erasure, homophobic and transphobic violence that is rarely dealt with, and discrimination make it difficult for LGBTQ2 youth experiencing homelessness to access shelters, resulting in queer and trans youth feeling safer on the streets than in shelters and support services.

Family rejection, inadequate social services, and discrimination in housing, employment, and education make it difficult for LGBTQ2S youth to secure safe and affirming places to live. Widespread homophobic and transphobic discrimination and violence in shelters and housing programs have resulted in an underrepresentation of LGBTQ2S youth accessing such programs. The need for LGBTQ2S specific services and housing options has been left unaddressed and unmet for far too long.

Even though it has been known for over two decades that LGBTQ2S youth are overrepresented amongst homeless youth and often feel unsafe in emergency shelters and housing programs; this issue has only recently entered important dialogue on youth homelessness, both nationally and internationally. It has taken many years to convince key decision makers that targeted responses and specialized housing options are necessary in order to meet the needs of this population of young people.

When I first started addressing the issue of LGBTQ2S youth homelessness approximately ten years ago, there was minimal discussion and interest related to this issue. Over the years, I have witnessed a significant shift regarding people’s understanding of LGBTQ2S youth homelessness and people’s willingness to discuss and address these problems. For example, Canada’s first transitional housing program for LGBTQ2S youth recently opened in Toronto; an essential service that has been long awaited for by young people and advocates across the country.

We have also seen new policies and standards, and both Municipal and Provincial government have started to respond to these issues. In 2015, I worked with the Government of Alberta to develop a strategy to meet the needs of LGBTQ2S youth across the province of Alberta. This work was grounded in research, community led, integrated throughout the Alberta youth plan, and rural and urban in focus. In response to some data that was collected at the beginning of this project, and to encourage interagency collaboration and build partnerships amongst services, one of the first steps included developing a provincial LGBTQ2S working group. It is essential for communities and young people to be involved in the development of strategies and services that are meant to support them.

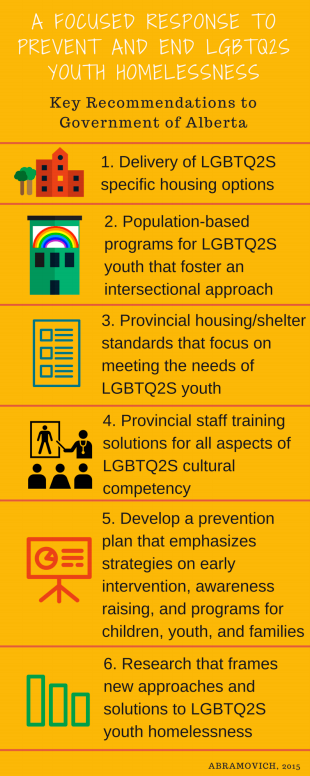

My final report to the Government of Alberta culminated in six key recommendations that were developed with the support of the Provincial LGBTQ2S Working Group, whom were engaged every step of the way. The recommendations align with and support the Alberta Youth Plan, and are reflective of current needs of the youth serving sector, including housing programs and shelters, across the province. These core recommendations are:

- Support the delivery of LGBTQ2S specific housing options (*development of new housing options and/or refinement of existing housing options).

- Support the delivery of population-based programs for LGBTQ2S youth that foster an intersectional approach (*development of new programs and/or programs within existing services).

- Create provincial housing/shelter standards that focus on working with and meeting the needs of LGBTQ2S young people.

- Develop integrated, provincial training solutions for expanded staff training for all aspects of LGBTQ2S cultural competency.

- Develop a prevention plan that emphasizes strategies on early intervention, awareness raising, and programs for children, youth, and families.

- Develop the capacity for research that frames new approaches and solutions to LGBTQ2S Youth Homelessness.

The recommendations emphasize the importance of working across government and sectors, as well as engaging with the communities and young people affected most by these issues, in building solutions. The core recommendations develop a standardized model of care, which will: (a) help meet the needs of LGBTQ2S youth at risk of or experiencing homelessness in Alberta; and (b) ensure that this population of young people are served more appropriately across the province. Most importantly, these recommendations will help design an effective systemic response to LGBTQ2S youth homelessness.

LGBTQ2S youth need to be prioritized because the common one size fits all approach does not actually work, because we know that one size does not fit all. If we are going to appropriately respond to youth homelessness, we need targeted responses for specific sub-populations of young people that are disproportionately represented amongst homeless youth.

Although it has taken many years to convince key decision makers to take action, we are starting to see innovative practice and policy changes, and this issue is finally starting to receive the attention that it so desperately requires. But there is still much work to be done, so, may we continue the important fight to end LGBTQ2S youth homelessness globally.

References

Abramovich, I.A. (2012). No safe place to go: LGBTQ youth homelessness in Canada-Reviewing the literature. Canadian Journal of Family and Youth, 4(1), 29-51.

Cochran, B. N., Stewart, A. J., Ginzler, J. A., & Cauce, A. M. (2002). Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: Comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 773-777.

Ray, N. (2006). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth: an epidemic of homelessness. Retrieved from http://www.thetaskforce.org

Quintana, N. S., Rosenthal, J., & Krehely, J. (2010). On the streets: The federal response to gay and transgender homeless youth. Retrieved from http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2010/06/pdf/lgbtyouthhomelessness.pdf

Denomme-Welch, S., Pyne, J., & Scanlon, K. (2008). Invisible men: FTMs and homelessness in Toronto. Retrieved from http://wellesleyinstitute.com/files/invisible-men.pdf

[1] This term is culturally specific to people of Aboriginal ancestry and refers to Aboriginal people who identify with both a male and female spirit. This term is not exclusive to gender identity, and can also refer to sexual orientation, and cultural identity.

This post was republished with permission from FEANTSA's Homeless in Europe - Spring 2016 magazine.