The headline in the Saturday Globe was disturbing enough: Residents of Toronto public housing four times more likely to be murder victims.

But I found myself equally rattled by the 285 on-line comments that followed. There were vitriolic references to “welfare bums,” the “psychiatrically deranged,” “gang-bangers, drug dealers, crack whores and other miscreants.” But if I looked past the mean-spiritedness, I could see a consensus opinion that even progressives might share: that social housing is simply unworkable, and that low-income neighbourhoods – especially those with black majorities -- will inevitably be breeding grounds for crime.

Earlier this year, I read a book that challenged this view. It is the tantalizingly-entitled When Public Housing was Paradise, J.S. Fuerst's compilation of 79 first-person accounts from people who lived or worked in Chicago’s public housing in the 1940s to 1970s.

The communities created by the Chicago Housing Authority were all, by current wisdom, destined to fail. The new-built estates were large and isolated – Regent Park-style low-rises punctuated with high-rise towers. They were overwhelmingly black communities, drawn from the tenements on Chicago’s South Side and migrants from the southern US. They were not mixed-income communities either. The CHA selected families – one third of them women-led -- exclusively from the bottom third of the income scale.

An incubator for leadership

Yet Fuerst credits public housing for creating Chicago’s black middle class, providing an “incubator for leadership” for African Americans. Account after account describes the children of stockyard workers and unemployed widows who are now lawyers, teachers, business leaders, police officers and senior public officials.

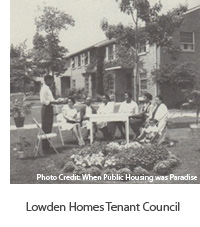

What made Chicago Housing Authority a launching pad to success? The tenants’ stories are filled with praise for the clean, well-managed buildings and grounds, where prizes were given for the best gardens. They spoke about housing managers who knew everyone’s name, encouraged local initiatives, and found jobs for teenagers. They spoke about the schools, churches, clubs, sports teams, and womens’ associations that were integral to the community’s strength. And they talked about the community itself, where everyone would look out for local children, and did not hesitate to pick up the phone if they spotted trouble.

Paradise lost

Today, public housing in Chicago and elsewhere is seen as anything but paradise. What went wrong?

The answers offered by the CHA’s former residents and staff will induce squirms in Toronto’s right- and left-wing readers alike. Here they are:

Abandoning tenant screening.

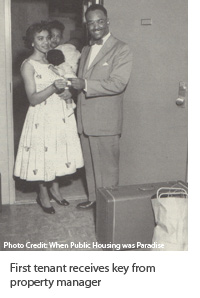

In CHA’s early days, preference was given to applicants with the lowest incomes in the worst housing conditions. But only those prepared to pay their rent, keep their homes clean, and supervise their children were accepted.

Once in the housing, the management strictly enforced standards, and so did other tenants. As one tenant recalled, “We kids cleaned those halls. And if somebody messed up our hall, we were quick to tell them, ‘Get that paper off that floor. Don’t you do that on my stairs, cause I got to clean it Saturday.’”

By the 1970s, federal rules forced CHA to give preference to the poorest of the poor, with no other screening. Today, tenants and former tenants quoted in the book say that “destructive and dangerous” tenants – anywhere from 10 - 30 per cent of tenants – need to be evicted to allow a return to healthy community life. Draconian as this move is, they argue it would be less disruptive than Chicago’s current practice of evicting all tenants to demolish entire buildings.

The introduction of income limits.

Public housing originally offered affordable rents for working families. But when a rent-geared-to-income system was introduced in the late 1960s, working families received a rent hike with each pay increase, and the most successful families moved out. Public housing was transformed from successful working class communities to the “people left behind.”

The loss of visionary leadership.

The Chicago Housing Authority’s first Executive Director, Elizabeth Wood, gathered around her an energetic team of the “brightest and best.” But in 1954, she was dismissed, ostensibly for “management inefficiency,” but more likely because her anti-segragation convictions put her at odds with her board.

After her departure, the most talented staff became demoralized and drifted away. To return to its former success, says Fuerst, public housing would need a cadre of employees with the same dedication, competence and sense of mission as the early staff.

What about us?

Chicago in 1950 is not Toronto in 2011. Yet we have too have a contingent of striving families, many of them immigrants, who are poorly-housed with very low incomes. We too have seen the decline of stable working class neighbourhoods into “the housing of last resort” – quite possibly for the same policy reasons that led to decline in Chicago’s public housing.

So what if . . .?

What if we explicitly designed public housing to vault low-income families into middle-class success?

- What rent polices would we set? How would we create opportunities to build savings?

- What institutions would provide the “incubators for leadership?”

- Would we be prepared to favour “strivers” (to use Fuerst’s term)? And if we did, what about those who don’t make the cut? Could we accept that private rental housing, or shelters, or the couches of family and friends, would become the real “housing of last resort?”

Well, what do you think?

Joy Connelly started working in social housing 30 years ago doing street outreach in downtown Toronto. Since then she has managed a housing co-op, developed new co-ops, and acted as the communications manager for the Ontario Non-Profit Housing Association. Over the past ten years, Joy has worked as an independent consultant on over 130 projects for federal, provincial and municipal agencies and many social housing providers. Joy's blog, Opening the Window, provides fresh ideas for social housing in Ontario.