We received this question via Shawna E. from via our latest website survey.

For some now, we’ve known that our early experiences – from prenatal to 8 years of age – have huge impacts on the rest of our lives. As Fox, Levitt and Nelson (2010) wrote:

There is increasing evidence that environmental factors play a crucial role in coordinating the timing and pattern of gene expression, which in turn determines initial brain architecture….Each one of our perceptual, cognitive, and emotional capabilities is built upon the scaffolding provided by early life experiences.

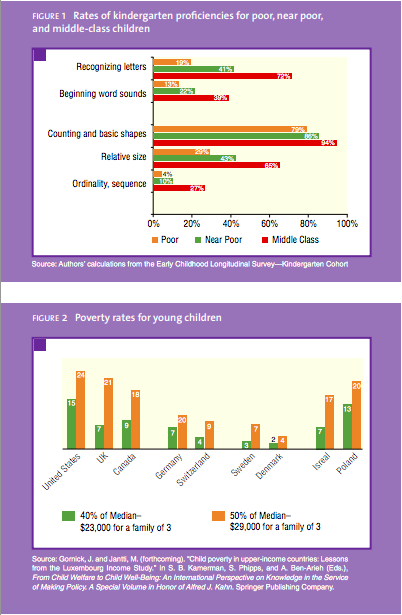

Building attachments and exploring the world around us are very important to our mental, physical and emotional development, which is unfortunately, not always possible when we experience homelessness and/or poverty. Children with these experiences are at risk of multiple negative consequences: infectious diseases, poorer educational attainment (as pictured right), injuries, lead poisoning, mental health & behaviour problems, malnutrition and stunted growth, anemia, dental health issues, immunizations, asthma, vision problems and abuse. Though slightly dated, a Healing Hands report from 2000 summarizes findings from some research on early childhood development and homelessness:

- “Almost half of school-age children and over one-fourth of children under five suffer from depression, anxiety or aggression after becoming homeless.

- More than one-fifth of homeless children 3-6 years old have emotional problems serious enough to require professional care.

- Homeless children are twice as likely as poor housed children to have learning disabilities, and three times as likely to have emotional and behavioral problems.

- The strongest predictor of emotional and behavioral problems in both homeless and housed poor children is their mother’s level of emotional distress. Over 60% of homeless mothers have been violently abused, and 45% have a major depressive disorder.

- Nearly half of school-age homeless children have witnessed family violence, and one in five become homeless because of it.

- Homeless children are physically abused at twice the rate of other children.”

This is a situation far too many families find themselves in. According to the State of Homelessness in Canada 2014 report, nearly 1 in 5 households experience extreme affordability issues. This means that they make low incomes and spend more than 50% of their earnings on housing – making them precariously housed. Due to an unstable job market that prioritizes low-wage and temporary jobs, a lack of affordable housing and countless other issues, families with children make up an increasingly large part of Canada’s homeless population. And as Hernandez, Schultz, Stambolis, Truax and Wilcox note in their case study on 7-year-old John, shelters are hardly ideal places for families with young children due to:

- “Limited access to kitchen facilities for food preparation

- Lack of safe places for children to play with parents or one another

- Lack of storage space for personal belongings (i.e., clothes, toys, books)

- Increased noise due to the volume of residents

- Limited support to care for children (some shelters discourage socializing among residents or prohibit shared child care)

- Pressure on families to keep their children quiet”

Furthermore, financial and emotional stress, plus preoccupation with survival, has severe impacts on people’s parenting abilities.

Timing is also important

It isn’t homelessness and poverty alone that result in problems for children – it’s the timing of these experiences. In the words of Duncan and Magnuson in their report, The Long Reach of Child Poverty:

It is not solely poverty that matters for children’s outcomes, but also the timing of child poverty. For some outcomes later in life, particularly those related to achievement skills and cognitive development, poverty early in a child’s life may be especially harmful. Emerging evidence from both human and animal studies highlights the critical importance of early childhood in brain development and for establishing the neural functions and structures that shape future cognitive, social, emotional, and health outcomes. There is also clear evidence emerging from neuroscience that demonstrates strong correlations between socioeconomic status and various aspects of brain function in young children.

Perlman and Fantuzzo’s interesting 2010 study examined public shelter use and child welfare data to determine the timing and influence of maltreatment and homelessness on children’s well being. They discovered that age at first maltreatment had a stronger influence on children’s academic achievement than homelessness – those who experienced maltreatment first as an infant on average had poorer second grade outcomes than peers who did not.

Of course, homelessness itself (like poverty) is the result of a complicated set of circumstances. Vineeth recently wrote about the effects of “adverse childhood experiences” (ACEs), which include abuse, neglect and household dysfunction (mental illness, divorce etc.). The U.S.-based ACE Study found that out of 17,000 participants, over 60% had at least one ACE. Back in 1997, another study concluded that ACEs like abuse and neglect are powerful risk factors for adult homelessness.

How can we reduce child poverty and homelessness?

So far, most of our interventions have been short-term and shortsighted. Simply removing children from poor households doesn’t change the fact that poverty and homelessness are big, ongoing problems. As my colleague Tanya wrote in her blog post, “Do we have a child poverty epidemic?”, these are issues that affect children because entire families are struggling:

Families can’t afford housing, they can’t afford food, they can’t afford healthcare; they can’t afford so many of the basic necessities of life. It’s not a matter of a handful of people slipping through the cracks…there are big, Canadian-winter sized potholes sucking people in.

As the Star story shows, poverty is also very racialized in this country. Immigrants, refugees, racialized Canadians and indigenous families are earning less than Caucasian families. This is not a new phenomenon either.

The adverse effects of poverty and homelessness can only truly be addressed if we do so directly, through making changes like: raising minimum wage and social assistance; increasing available long-term and stable jobs; and creating more affordable housing.

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.