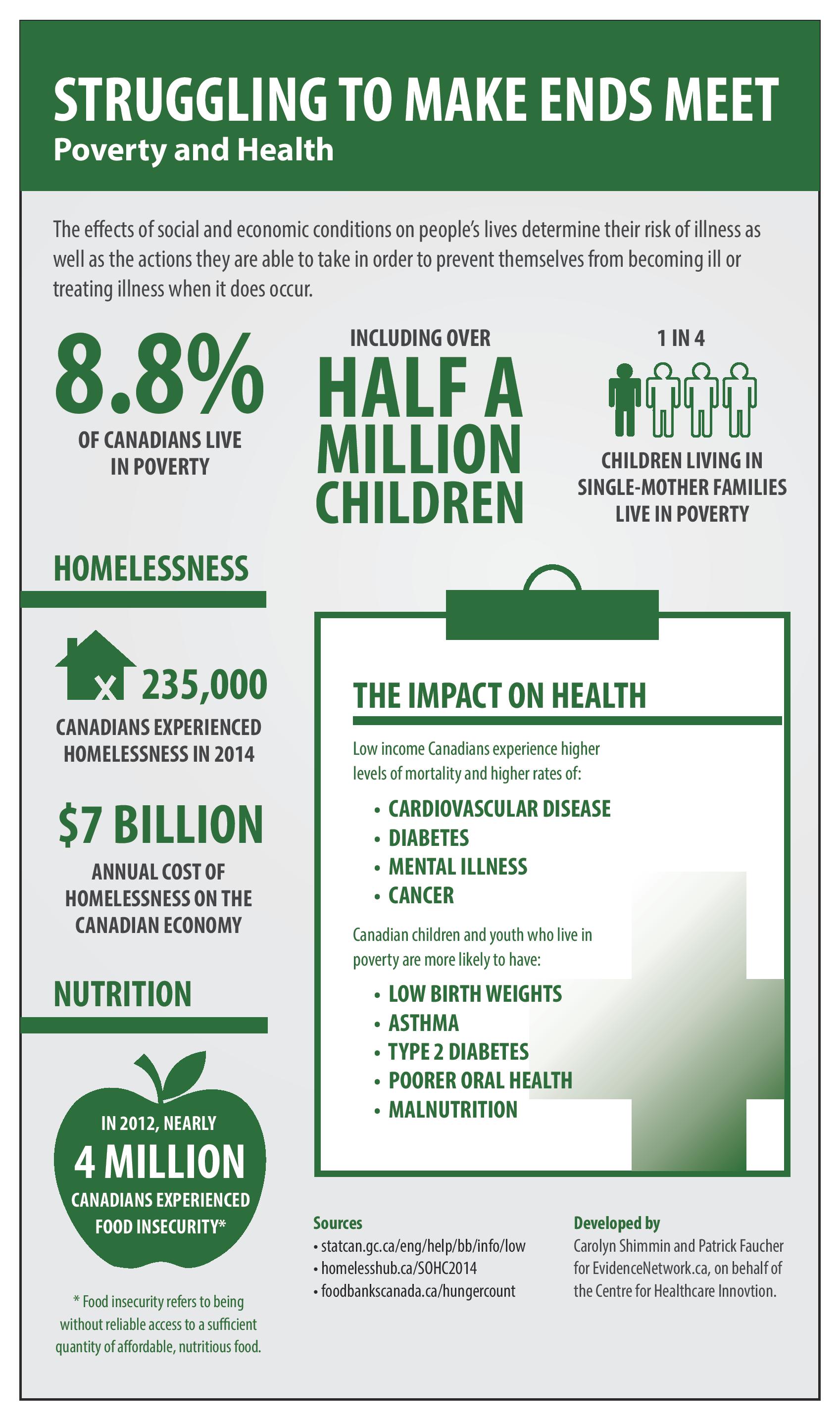

Poverty and poor health outcomes are inextricably linked. The below infographic, published by the Evidence Network, takes a look at the prevalence of poor social and economic conditions in Canada, and the impact that these conditions have on health.

The infographic, sourcing figures obtained from a Homeless Hub report, states that 235,000 Canadians experienced homelessness in 2014. The infographic also states that nearly 4 million Canadians experienced food insecurity in 2012. Housing and food security are just two of several social determinants of health that exists. The term social determinants of health is used to refer to socioeconomic conditions that shape the health of individuals, communities and jurisdictions. These social determinants include education, employment, accessibility to health services and race.

Aboriginal Status

One important social determinant of health commonly overlooked, and not mentioned in the infographic, is Aboriginal status. Many homes on Aboriginal reserves can be described as critical housing situations, as they often lack basic sanitation and access to clean water: fundamental health risks in their own right. Furthermore, Aboriginal Peoples in Canada are up to four times more likely to be living in crowded housing than non-Aboriginal people. Aboriginal households are more likely to have food insecurity than non-Aboriginal households. A history of colonization has resulted in Aboriginal Peoples having little control over policies that impact them directly.

Cumulative Effects

Cumulative effects refer to the accumulation of advantages and disadvantages for an individual over time. The infographic states that over half a million Canadian children live in poverty. We need to consider how living in poverty places these children at a disadvantage from the onset of life. The quality of early childhood conditions contribute to health and well-being in the short-term, and are also independently linked to adult health outcomes. It is also important to remember that advantages and disadvantages related to wealth have the potential to interact.

For example, nutritional deficiencies in early childhood may lead to a lack of neural development for a young child living in a low-income household, resulting in a developmental disability. The absence of adequate childcare and the right educational supports for this child can interact with a developmental disability to lead to very poor long-term social and health outcomes over the lifespan. Children from wealthier families with development disabilities are more likely to be able to afford specialized services and treatment not covered by existing provincial and federally funded health services. Examples of poor health outcomes that can have cumulative effects on the lifespan include early onset diabetes, developmental disabilities, and learning disorders.

Attributing Health Disparities

Health disparities between individuals are largely attributed to biomedical determinants of health (ex: genetics) or “lifestyle choices” made by individuals. Such attribution make light of the role that low incomes play in poor health outcomes, and instead attribute the presence of illness to luck, treatment options and poor decision-making by individuals. There is a direct link between socioeconomic status and health. This positive correlation holds true not only when comparing the most disadvantaged with the least advantaged, instead research demonstrates the presence of a social gradient in health. For many diseases, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase in income correspond directly with improvement in healthcare outcomes. If we are serious about improving health outcomes for all Canadians, it is essential that we target social and economic conditions by taking the social determinants of health seriously.