This question came from Chris M. via our latest website survey:”What considerations should we explore when looking at sexual and gender identity and homelessness?”

Gender and sexual identities are very important considerations when it comes to the experience of homelessness and how we, as housed people, researchers and frontline workers, approach people. The following are a few considerations I would rank highly, but this isn’t an exhuastive list. I welcome additions in the comments!

Gender and sexual identities are diverse, varied and complicated

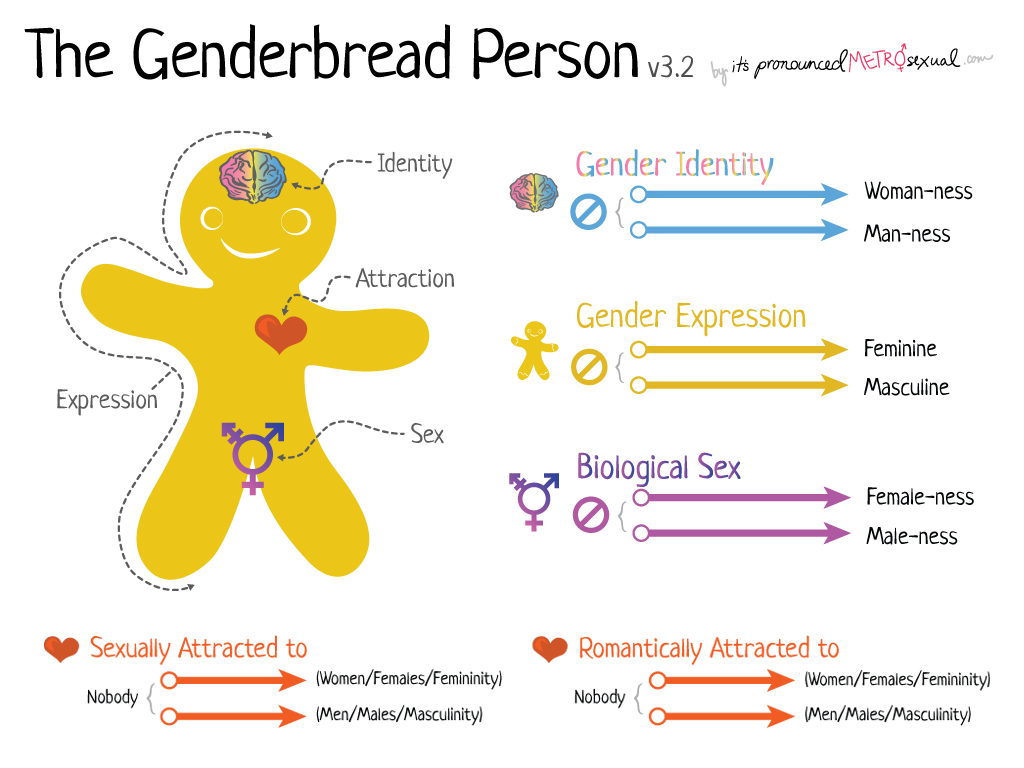

Sexual identity refers to the labels we give ourselves based on our sexual identity (ie. straight, queer, gay, lesbian), while gender identity reflects how we understand our gender (ie. man, woman, trans, genderqueer, gender non-conforming, etc.). There’s another important term here: gender expression, which refers to how we present our gender (femme, butch, masculine, feminine, androgynous, etc.).

I’ve included the Genderbread Person by Sam Killermann to help illustrate all the different ways people can identify. As you can hopefully see, people have a variety of identities and expressions that all intersect, and not necessarily in predictable ways.

Despite all of these possibilities, most of our society (and our homelessness sector) is set up in a way that only accommodates two categories of people at any given time – think about how we organize public washrooms – and therein lies the core problem.

Discrimination is an ongoing issue

There are two major sources of the ongoing discrimination of LGBTQ2 people: heterosexism (the belief that being heterosexual is assumed and “natural”) and gender binarism (the belief that there can only be two genders; and some would argue that they correspond with birth sex). Despite decades of progress and awareness, these ideas still very much persist. This often produces environments in which people who don’t identify within expected categories (ie. straight man) face stigma, discrimination, harassment and abuse. When people with non-heterosexual and non-cisgender – being cisgender means that your gender identity corresponds with what is generally expected with your corresponding assigned sex –identities experience homelessness and the vulnerability and stigma that comes with living in poverty, these issues can be compounded and made worse.

This is especially true for people who are transgender. 20% of respondents to the Ontario Trans Pulse survey indicated that they had been sexually or physically abused for being trans, and 13% said they’d lost jobs because they were trans. An estimated 1 in 3 transgender youth are turned away from shelters because of their gender identity and/or expression; and face more discrimination than any other youth group. Many shelters are segregated by birth sex and have gendered rules about intake/showering/dress, which can be difficult for youth who are trans or gender non-conforming. In one report, Toronto agencies stated that they faced great difficulty in serving trans youth. (Good news: the city has opened Canada’s first LGBTQ2 specific youth housing!)

Another issue that trans and gender nonconforming people face is identification and acknowledgement. People often struggle to get appropriate identification in their chosen names and correct gender identity, which is important if they want to do, well, anything in a society as document-reliant as ours.

I. Alex Abramovich has an excellent blog post that goes into greater detail on what trans people can face in the shelter system.

Women and feminine-identified people face unique issues

There are issues among people who identify along the gender binary as well. Single men have long been reported as the largest group of people who are homeless, but there is a growing number of women who are or who are at risk of becoming homeless. The National Shelter Study (2005-2009) reported that just 26.7% of shelter users were female, but these numbers don’t include shelters for women fleeing violence, nor do they include women and families who do not use shelters or are hidden homeless. It also doesn’t draw attention to the fact that Aboriginal women are overrepresented in the homeless population.

As I’ve written before in posts about senior women and single-parent families, women are at a greater risk of some of the socioeconomic factors that contribute to homelessness: more temporary, underpaid and part-time work; and increased risk of intimate partner violence; and at a higher risk of living in poverty. And as we’ve addressed in our section on single women, poverty doesn’t impact all women equally:

- Aboriginal women (First Nations, Metis, Inuit) – 36%

- Visible minority women – 35%

- Women with disabilities – 26%

- Singe parent mothers – 21% (compared to 7% of single parent fathers)

- Single senior women – 14%.

- Single mothers: 51.6% of lone parent families headed by women are poor

There are so many more factors beyond gender and sexual identity – and indeed, well beyond the individual – that can contribute to poverty and homelessness.

So what should we as frontline workers and researchers do?

- Be explicitly LGBTQS positive, so people in need know where they can go (hang rainbow flags, posters with equity policies, etc.).

- Help foster an openly LGBTQ positive culture where you live and work. This means dispelling misconceptions about sexuality and gender, not tolerating hateful language, having difficult conversations with people who have negative opinions and maybe even sharing the Genderbread Person around a few times.

- Don’t make assumptions. If you’re not sure how someone identifies or how to address them, just ask! Or always opt for a gender-neutral term like “they.” Remember that people may go by different names and/or pronouns depending on context, so asking is always the safest route.

- Be aware of the issues that people face not only due to their gender and sexual identities, but their expression, race, class and ethnicity as well.

- Change organizational processes and policies to acknowledge differences in gender and sexual identities (ie. allowing more options than “male” and “female” on forms), and be understanding of documentation being missing/incorrect/out of date.

- Do not unnecessarily divide people based on gender identity (ie. “male” and “female” only washrooms present enormous challenges for trans and gender non-conforming folk).

We can also consult some of these amazing resources, many of which were created with LGBTQS people themselves:

- Toolkit for Practitioners Working With LGBTQ Runaway and Homeless Youth

- LGBTQS Toolkit

- A Place Just For Us So We Can Feel Safe: Learning to Better Serve LGBTQI2-S Youth

- Quick Tips: Working with LGBTQI2-S Youth Who Are Homeless

This post is part of our Friday “Ask the Hub” blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.